Utopia is not a popular genre. The number of modern utopian novels is miniscule compared to its opposite, dystopia. People often struggle to think of what a utopian story would look like. How could the characters be relatable? What’s the conflict in a world defined by having less conflict? After reading some of the most influential utopian novels of the past century, I found out how authors handled the issue of what conflict and character work looks like in utopian settings. Before discussing what these story structures are, let’s address some misconceptions. Utopia does not mean perfect in everyway imaginable. Utopia also does not mean world that seems perfect but is actually bad (that is just dystopia). Utopian novels are still fiction and are not, usually, an author’s policy recommendations for how humans must live. It is better to think of utopian worlds as thought experiments that explore alternative ways humans could organize a society.

Journalist Writes About Isolated Society

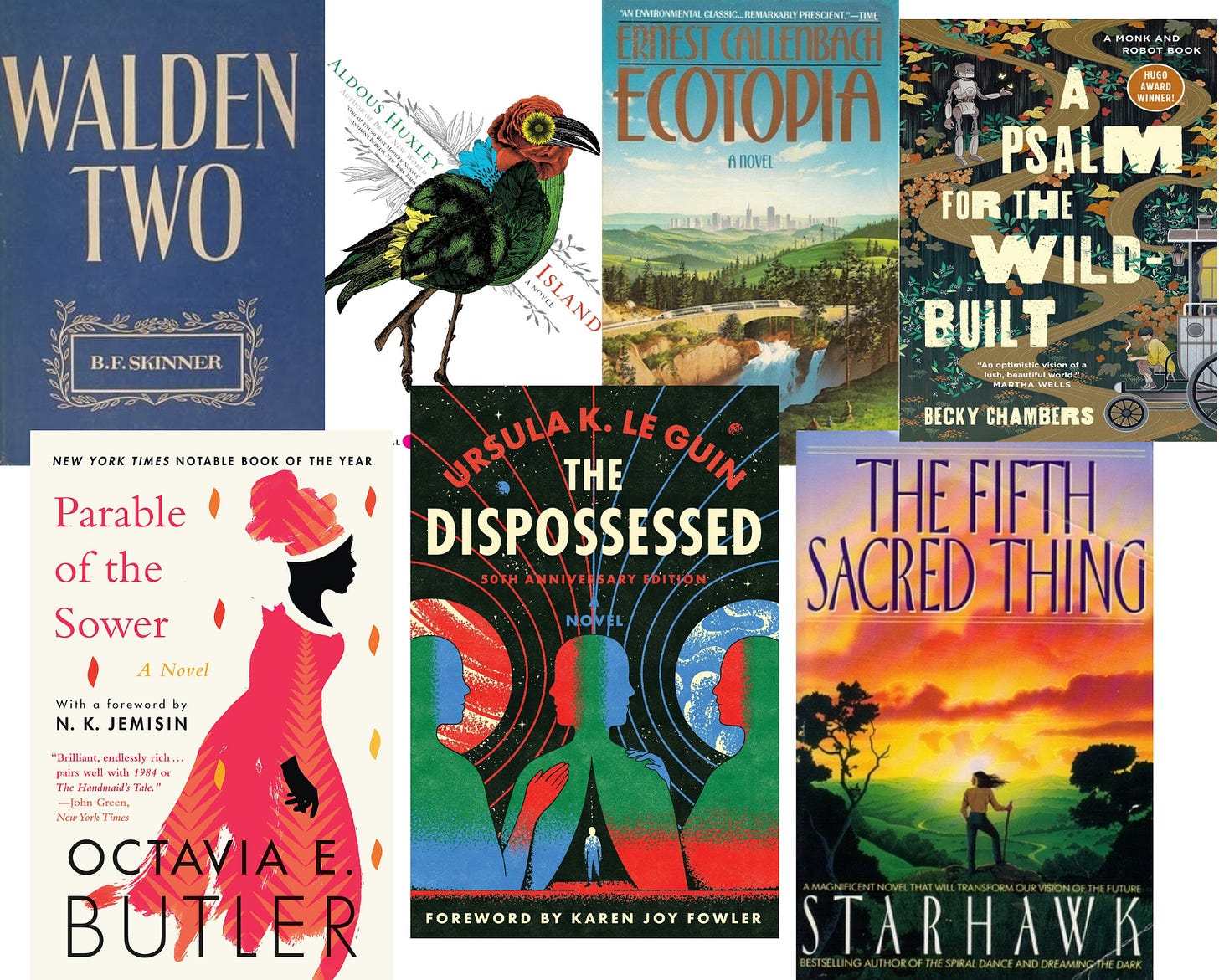

Most of the earlier utopian novels I read used this structure including B.F. Skinner’s1 Walden Two (1948), Aldous Huxley’s The Island (1963), and Ernest Callenbach’s Ecotopia (1975). In The Island and Ecotopia, the main character is a journalist tasked with writing a story about a famous yet secluded community rumored to be an idyllic paradise. In Walden Two, the main character is a professor who visits a nearby utopian community out of personal and academic interest. Even though he is not a journalist, the story structure is similar to the other two. In all of them, the protagonists are skeptical of the communities they are visiting due to their background of journalistic or academic objectivity. They serve as audience stand-ins who have plot-related reasons to run around asking questions about how this utopian society works. These novels mainly consist of long explanations about the world. Another name for this structure could be Exposition: The Novel.

Walden Two barely pretends to have a plot. Like all of these books, the main character debates whether to join the community but, unlike the other books, there isn’t much beyond that. Ecotopia is an epistolary novel where each chapter includes an article the journalist wrote and his diary entries showing his personal experience in the country of Ecotopia. The diary entries add more of a plot than Walden Two but, unfortunately, it’s not a great plot.2 The Island is the best in regards to having relatable characters and conflicts, which shouldn’t be surprising since Huxley was the only one of these three who wrote other fiction books. His journalist has an ulterior motive and a tragic backstory. Even so, I can see why Brave New World is much more popular than The Island.

Even though none of these books are great at the typical things we associate with good fiction, these books have been hugely influential. Walden Two become the direct inspiration for an intentional community, Twin Oaks, which was established in 1967 and is still around today. Twin Oaks is a radical community where everyone shares an income through community-owned businesses. While much of the system from Walden Two proved unrealistic, Twin Oaks still uses a work credit system from the book. Everyone must put in 42 hours a week (in the book it’s four) but those credits include domestic tasks and childcare so everyone at Twin Oaks works less than the average person. Ernest Callenbach was very involved in the eco-village and communal living communities as well as environmental activism. Ecotopia was a major cultural touchstone for hippies everywhere as can be seen by the various think pieces about the book’s impact after Callenbach’s death in 2012.

The success of these novels show that utopian stories can do well even without relatable characters or engaging plots. Sometimes a good idea is enough. People will forgive long exposition if it is interesting and inspiring. Part of me feels bad for criticizing these novels, which so many love, but part of the reason I feel comfortable doing so is because the other novels I read did a much better job at presenting an interesting world while also being fun reading experiences.

Defense Against Outside Forces

Another trope is a utopian community needing to survive against the attacks of a dystopian society. Two examples include The Fifth Sacred Thing (1993) by Starhawk and Parable of the Sower (1993) by Octavia Butler. These two books are remarkably similar from the year of publication to the story structure and themes. Both books are initial entries into series that expand on their worlds while also being optional to the reading experience (i.e. the first book has a satisfying ending that does not require reading further). In both series, the US has turned into a hellscape where capitalism is at its worst extreme. The poor are poorer than ever. They have little access to food, water, and shelter without agreeing to slavery-like arrangements. In both series, there is a community based on a nature-centered spirituality that provides its members with basic necessities allowing them to not only survive but to thrive. Both series are dark in tone. The utopian world provides hope but it’s a precarious hope that must be upheld despite the horrors that plague both novels.

There is also a magical component to these worlds that is not present in any of the other utopian novels I read. Starhawk is primarily known for her paganism and The Fifth Sacred Thing is undoubtedly a pagan book. I still included the book here because Starhawk was very interested in the logistics of how a better society could work. The magic is part of the story but is not essential to running a better society. The parable series has only one fantasy element—the main character is an empath who feels the pain of anyone she sees due to her mother’s addiction to a fictional drug during pregnancy. Her empath ability is a power and a hindrance that is central part of her character. Despite the many commonalities, the books are different in scale and plot structure. In the Fifth Sacred Thing, there are three viewpoint characters who are from a utopian community that is well established and has existed for over twenty years at the start of the novel. In Parable of the Sower, there is only one viewpoint character and the story is about her growing up, developing a nature-based religion, and establishing a utopian community despite the steep obstacles in her way.

The structure of trying to survive against a hostile world makes for an engaging read. Writers may have an easier time writing a story like this since the structure is more similar to the average dystopian novel. These books are great but the dystopian elements often overshadow the utopian parts. The Fifth Sacred Thing and Parable of the Sower are heavy books where characters die, and there’s lots of racism/sexism/classism. If you want something because it is a hopeful read then I’d suggest any of the other books in this post.

Existential Crisis in Paradise

The last category are character-focused novels where the main conflict is an internal struggle faced by the protagonist who lives in a utopian setting. Two examples include the Monk and Robot series by Becky Chambers and The Dispossessed by Ursula K Le Guin. The former is about a solar punk world where everyone’s basic needs are met and they live in environmentally sustainable ways. The main character is a monk named Dex who is trying to figure out what type of monk they should be and what their broader purpose is. The Monk and Robot series is about how a person finds a sense of meaning in a world of plenty where everyone’s basic needs are met. There are still jobs to do but the same problem many face today of how to decide what to do is something Becky Chambers imagines would still exist in utopia.

The Dispossessed is Ursula K Le Guin’s take on what it would look like if anarchists had a successful revolution and achieved the society theorized by people like Peter Kropotkin. Shevek is the main character. He lives on an anarchist moon colony called Anarres a couple of generations after their succession from the hyper-capitalist, materialist world below. The book is about Shevek’s struggle with the increasingly dogmatic way people treat the anarchist principals of his society and the temptations offered by the more glamorous society they succeeded from. The central theme is how do people continue to create and maintain a utopian world without falling into the same problems as the world they left.

What these books have in common is that the authors explore problems that would arise in the utopian settings they created. They allow problems to exist based on assumptions about human nature rather than concoct a sci fi device that solves everything. Dex struggles with finding meaning because allowing people to choose their role in society will always mean doubt about that choice and this is not something fixed by an omniscient computer program or a mystical elder who knows what everyone is best fit to do. The people of Anarres stray toward simple slogans and binary thinking because that is easier to teach than nuance and deep understanding. Shevek wonders if the material abundance of capitalism is better than the simple yet guaranteed provisions on Anarres because Le Guin does not depict anarchism as a perfect solution nor anarchists as saints who care nothing for luxury.

The structure of existential crisis in paradise is my favorite for exploring utopian concepts. The stories are more engaging than journalist travels to utopia and it is more hopeful as well as more focused on exploring the logistics of utopia than defense against outside forces. The structure of focusing on problems that would arise in utopian settings also helps these books be less naïve. Of course they’re still imaginative works, but they are relatable and easier to believe in because the characters are still humans with human problems.

Other Possibilities

These are just the common themes in utopian novels that currently exist and are somewhat popular. There are endless ways to structure utopian stories from slight adjustments to these tropes to experimental stories that rely less on the idea that good stories need big conflict. For example, instead of a journalist, there could be a book about an anthropologist or a merchant or even a tourist who is visiting a faraway utopian community. Slice-of-life vignettes in utopian settings are common in shorter works and it could work well in long-form content too. Describing a simple life in an extraordinary place can be engaging. Going more into the conflict route, it would be fascinating to read a dystopian series that keeps going after the overthrow of an authoritarian regime and where the characters create something truly good rather than just something more humane than what came before. There’s so many options. Hopefully, we’ll get a utopian boom and the idea of writing a good story in a utopian setting will no longer seem so difficult.

Let me know if there’s any other utopian works that I missed. This was not a comprehensive list and simply reflects the utopian books I’ve read in the past few years.

Better known as one of the most influential psychologists of all time. He was a behaviorist focused on applying operant conditioning (positive vs negative reinforcement and punishment) in various ways. You certainly learned about him if you took any psychology courses. Walden Two is a utopian community based on the principals of operant conditioning and Skinner’s love of Henry David Thoreau’s Walden.

Ecotopia was the book that I was most disappointed with. It has aged poorly both due to being influential enough that what made it innovative is now standard in alternative eco-visions (such as right-to-repair and a transport system based on trains plus biking) and what’s been forgotten is bizarre and/or offensive (no emotional repression means people yell and fight each other regularly, the main character “rapes” his love interest out of jealousy though she seems to be fine with this, and there is racial segregation that is “okay” because it’s the minorities who choose to be separate).

The best Utopian fiction hasn't been written yet. My friend Max is attempting to write some. His structure so far is based on Hegel's dialectics: we're living in an imperfect (not ALL bad) dystopia, some hunter gatherers are living in an imperfect (not ALL good) utopia that is being encroached by the dystopia, and some syntopia emerges, also not a final state of perfection, but an evolving process that responds to real conditions, based on a better understanding of what ails us and what heals us.

Many of the anarchist utopian writers believed that what ails us is attempts by some humans (or other creatures) to dominate, oppress, and otherwise curtail individual liberty. But this is only one ailment, and what is becoming clearer to me and others (such as Daniel Schmachtenberger) is that capitalism is destroying or has already destroyed the coherence of integrated individuals, families, tribes and villages, federations of these, and nations. And that without these we have Climate Change, shallow relationships, loneliness, nature degradation, and a proliferation of war.

Intentional communities based solely on anarchist principles or opposition to oppression have mostly disintegrated, and those that still exist are not happy, vibrant or growing places. Even adding an environmental ethic seems to not be sufficient for IC well being.

Some books here I will have to add to my list! I love that you included Octavia Butler, in my very binary categorisation I would have always called that dystopian but I now see seeds of utopian vision existing in juxtaposition with dystopia is actually a clever way to make a utopian vision gripping! I’ve enjoyed many of Kim Stanley Robinson’s and I think they do a similar thing, struggling to remember a specific example right now! Xo