Over the summer, I went to the Building Museum in D.C. and saw the Capital Brutalism exhibit about the influence of the infamous architectural style in the city. Capital Brutalism was about how brutalist architecture became controversial and how architects could reimagine specific brutalist buildings in DC (most of which house government agencies) to better fit the current era. The exhibit seemed to align perfectly with my interests. In many ways, brutalism is the opposite of solarpunk. Brutalist buildings are undeniably human through it’s unusual shapes, monochrome colors, and lack of greenery while solarpunk buildings are colorful and surrounded by trees, bushes, and foliage. Solarpunk is about finding a better balance of technology and the natural environment while brutalism is about embracing modernity with no attention given to the natural environment.

Unfortunately, I found most of the imagined updates to be disappointing. I left the exhibit less sure that it was even a good idea to try to update these buildings. One of these reasons we’re in this environmental mess is the supposed need to renovate older things as beauty norms and standards change. In some cases trying to update something to be more environmentally-friendly is worse than just than just leaving it be. Brutalist buildings might not be sustainable to make, but it does not follow that the most sustainable thing to do is to change the buildings that already exist.

What is Brutalism

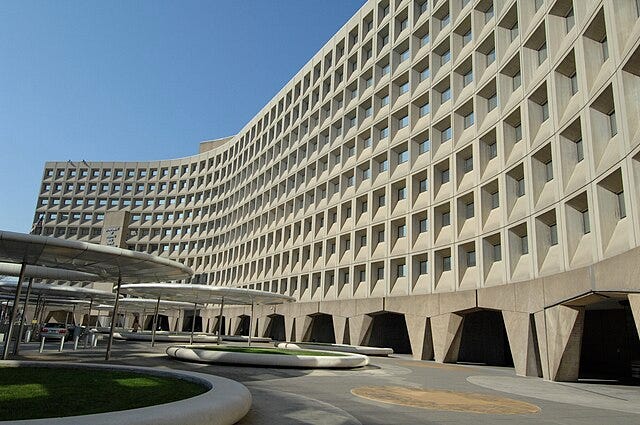

It is an architectural-style whose name comes from the French word for raw concrete. Two of the defining characteristics of brutalist buildings are that they are made of exposed concrete and consist of odd, geometric shapes. Brutalism was wildly popular in the mid-century starting after WWII and ending around the 1970s. Since that was a time of mass development in many parts of the world, the legacy of brutalism lives on even though few architects still build in the style (at least in the US).

While brutalism has always had its critics, it wasn’t that controversial until recently. People liked the unique style and the “honesty” of it. One of the artistic goals of brutalism was to create a building that didn’t pretend to be anything else hence why they used exposed concrete. You can think of fake brick sliding as the antithesis of what brutalist architects were trying to accomplish. While fewer people built in the brutalist style after the mid-century, it didn’t become widely hated until recently.

The cynic in me believes the decline in popularity of brutalism is because we live in a world where the appearance of something matters more than the reality of the thing, and where people are used to mass produced buildings that look the same no matter where you go. Brutalism is not my favorite style, but I appreciate it’s uniqueness and boldness. Visiting DC felt refreshing because no other city looks like it. The part of me that’s less cynical assumes brutalism became less popular because people want color and they realized humans are unhappy in concrete cities with little access to nature.

Putting Trees on Rooftops

Below are a couple of the architect’s depictions of alternative designs to brutalist buildings in DC. None of them are bad, but they did seem a better fit for a boardroom than a museum. I’d argue they are slight improvements rather than “reimaginings.”

I thought a lot about why these designs bothered me. These pictures could fit well on a solarpunk mood board and it’s a great thing to add more greenery to cities. What kept coming back to me was the fact that brutalism was not unpopular until recently. Is there a need to do anything to these buildings? Wouldn’t resources be better spent on more substantial improvements that help with accessing nature or increasing clean energy use?

While putting trees on rooftops is popular in depictions of a greener future, especially solarpunk ones, there is debate over whether doing so is a good idea. I came across the following quote by climate reporter, Tim De Chant from his article, “More reasons to stop putting trees on skyscrapers” that gets at why these reimaginings bothered me.

To me, trees atop buildings have become an architectural crutch, a way to make your building feel sustainable without necessarily being so. And that’s a charitable assessment. Here’s how I really feel—trees on skyscrapers are a distraction from rampant development and deforestation. They’re trees for the rich and no one else. They’re the soma in architecture’s brave new world of “sustainable” development.

Most attempts at adding greenery to buildings leads to a structure that is pretty to look at, but is resource intensive to maintain. That’s true of buildings designed to have plants on it so this is likely even more true of something whose purpose was always to be a raw block of concrete. This gets to the purpose of brutalism as a style that’s honest. Adding a few trees and bushes whose environmental benefits are very likely offset by their difficulty to upkeep is the opposite of architectural honesty.

Even though solarpunk is primarily thought of as an aesthetic there have always been calls to think of it as more than pretty futuristic images. From the beginning, the point was to imagine a future where energy is renewable, not just a future where cities are pretty to look at. For at least a year, anytime someone posted on r/solarpunk there was a mod-generated warning to watch out for greenwashing. Despite the constant warnings to not define solarpunk only as an aesthetic, there is still such a strong pull to do that. Just as what happens to all variations of punk, the edge gets taken off in order to reduce it to symbols that are easily sold and consumed. Simply putting a tree on a skyscraper is not enough to make something solarpunk or better aligned with an environmentally conscious future.

The Temple of Play

To demonstrate the difference between superficial and substantive change, I will end by mentioning my favorite part of the exhibit, “The Temple of Play.” One group of architects took a much more creative approach to the assignment. They reimagined not just what the building could look like but what’s its purpose would be. In this case, they wondered what it would be like if the US had a government department devoted to play. The Humphrey building would become the headquarters of this new department and instead of being only a place for the top brass to work, it would serve as a giant playground for anyone in the area— both child and adult. I loved the vision and I loved the concept. Instead of just adding trees to an existing building, the architects let their imagination run wild. It’s less practical, but this was an exhibit at a museum so it doesn’t have to be practical.

The Temple of Play does not easily fit on any solarpunk mood board. This reimagining does not address climate change, modernity’s relationship with technology, or the use of renewable energy. Even so it fits more with the solarpunk spirit than the other images did. An agency of play is a radical idea. Having an agency like this would involve the US government funding something that’s defined by its uselessness. It’s a humanist project that made me feel like I was seeing a world where the point of the government was to help its citizens live their best lives rather than narrowly focus on growing the economy, making sure the population is just healthy and educated enough to work, and building the military industrial complex. The temple of play shows a world of abundance and humanism, not scarcity and utilitarianism.

The architects who designed the Temple of Play were not concerned with updating the images of a once popular yet now hated architectural style to help it better fit aesthetic ideas of what sustainability looks like. Instead, they used this opportunity to better imagine a world where we collectively care about everyone living the good life. Their answer is not that we need to update the look of these buildings, but the content of them. There’s nothing deceptive about that.

Ooh I love the Temple of Play! We recently took Jules to Fernbank, and watched the IMAX: Cities of the Future. It was interesting, and now that I’m working where I do, I found myself wondering about this balance between making a difference and making the appearance of a difference…I think you younger people are going to make a real difference. If you ever see the movie, I’d be curious to hear your thoughts.

Ooh, I gotta figure out a way to get to DC before this exhibit closes. I actually kind of love brutalism, would definitely be bringing it back in my alternate life as an architect.